Architects the Prisoners of Dilemma

Michael Lewarne uses the Prisoner’s Dilemma to raise the issue of architects low balling fees and doing free work in order to win bids. What can be done to ensure architects value their work and reflect the true cost of projects when setting fees?

Preface: I’m no expert on Game Theory, nor a mathematician or psychologist. This post, using the Prisoner’s Dilemma to explain the behaviour of the architecture profession, is therefore limited in scope. It’s important to note that the Prisoner’s Dilemma explains a one-off scenario that is between two parties. The scenario I’m discussing is neither a one off or between two parties. This hasn’t prevented academics exploring scenarios of the Dilemma that are similarly complex. It’s therefore helpful in considering the challenges faced by the profession when choosing to do free work or discount fees.

The Prisoner’s Dilemma

The Prisoner’s Dilemma is a situation where the decision makers are incentivised to make a choice that results in an outcome that is worse for the individuals together. It’s typically explained in this way:

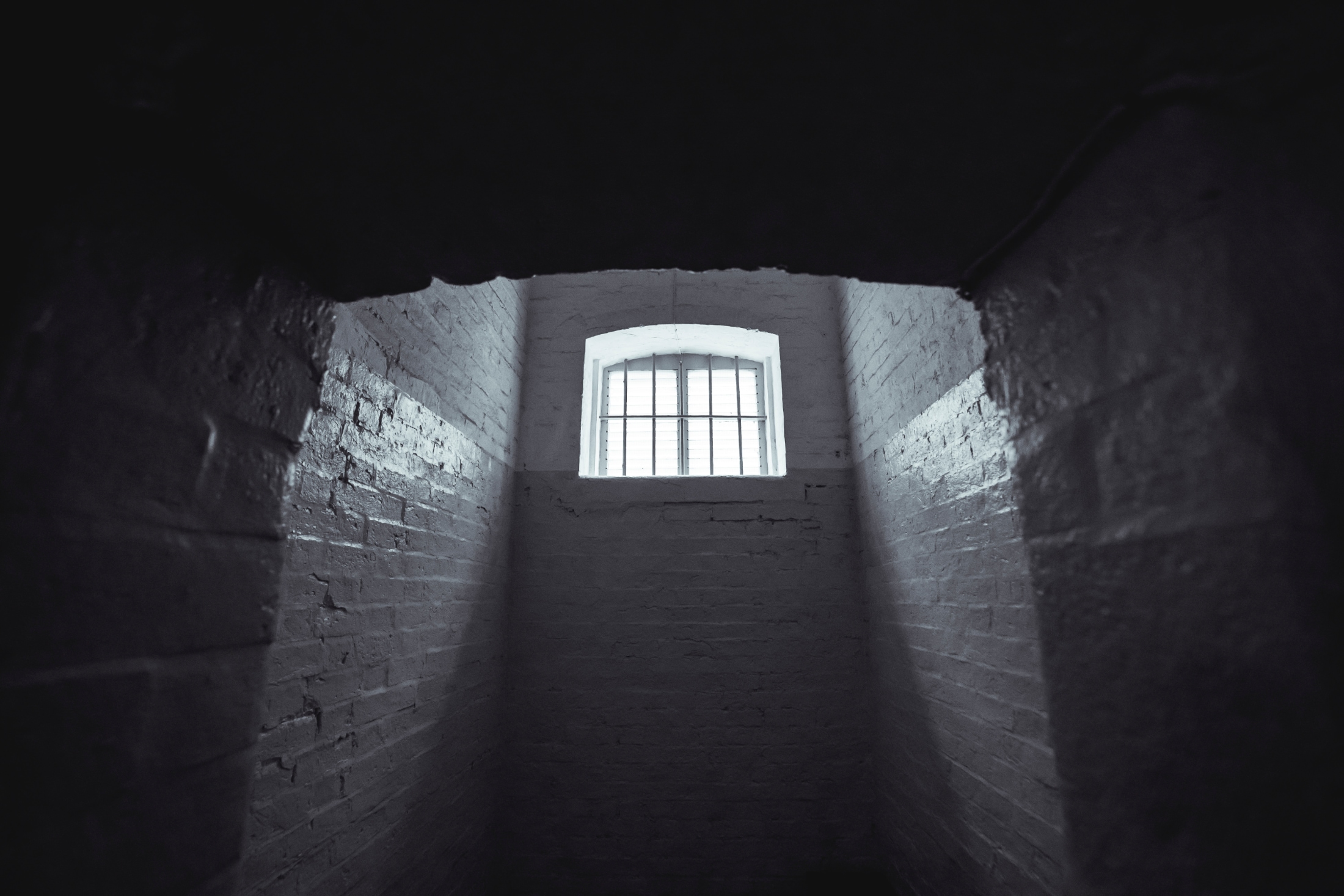

- Two members of a crime gang, Abe and Beatrice, have been arrested. They’re then subjected to separate interrogation.

- There’s no evidence against either and the only hope the cops have is to get one to grass on the other.

- Abe and Beatrice have a choice: stay quiet and maintain solidarity, or grass.

- If each stays quiet, the cops have got almost nothing. So, they’re looking at a year behind bars for a minor offence (a total of two years of gaol time for both).

- If one grasses on the other, the snitch goes free while the other gets five years (a total of five years gaol time).

- If they both roll over and grass on the other, they’ll each get two years (a total of four years gaol time).

It’s a scenario in which they both have an incentive to grass on each other, regardless of the other’s action. Considering Abe, for example, if Beatrice remains silent he has a choice of staying silent and getting one year in the slammer, or grassing on Beatrice and going free. Grassing is clearly the best option. Alternately, if Beatrice decides to grass on Abe, if Abe stays silent he’ll get five years. If Abe grasses he gets only two years. Again, the best option here is to grass.

The paradox of the Prisoner’s Dilemma is that if both Abe and Beatrice cooperate to stay silent, they each only get one year, minimising their combined gaol time to two years. Individually, however, as described above, the incentive is always to grass – thus, increasing the combined gaol time to four years.

The Architect’s Dilemma

Relating this to fees and/or doing work for free in order to win a project…

It’s not perfect, but let’s consider the scenario of a number of architects pitching for a project. They can put in a realistic fee or they can choose to low ball it or throw in some free work. The difference to the Prisoner’s Dilemma in this scenario is that there’s history, a history of other architects low balling and doing free work to win projects. The dilemma is, pitch a realistic fee and know you will almost certainly be out of the running; alternately, low ball the fees or offer up some free additional work up front and be in the running. In the second scenario, everyone loses. Those that pitched realistically have spent (ie wasted) time and money on a bid that has no likelihood of winning; those that low balled and offered free work are costing themselves additional money in order to “win” at a cost to the profitability of the project.

It’s clearly better for architects to cooperate and put in bids that reflect the true cost of doing the project and without giving away fees or work. Yet the incentive is always self-interest to try to win the bid.

Beating the Architect’s Dilemma

Game Theory suggests that there’s no way to beat this dilemma; self-interest will always be followed. The advantage the architecture profession has is that it’s served by more than self-interest, suggesting there may be some opportunities to challenge and change outcomes. This is because those seeking proposals from architects have the opportunity to become part of the solution, rather than an adversary. In considering this, I acknowledged institutional clients are better positioned and more likely to be receptive than private entities who are typically more governed by self-interest.

Ethical Bidding

A model bid process for Expressions of Interest, Tendering, etc, could be developed incorporating an equitable bid process. This would need to be based on an ethical and auditable template outlining the process. There could be an independent authority to outline requirements, be an arbiter of disagreement and certify the process. Architects (or other bidders) can follow due process and be reassured that bid caller and competitors alike are doing so too. Tenderers can be comfortable in the knowledge they are entering an equitable process.

Clearly this is not in the tenderer’s self-interest, but it might be something to be championed and adopted by government – setting an example and benchmark to be followed by private interests. If the profession was to similarly follow, refusing to enter non-certified processes, it may result in poor quality bids and outcomes for the private entities. Solidarity and cooperation driving change.

Trust

Cooperation relies on trust. If architects trust each other to remain in solidarity and not low-ball or give away work for free, then any project bids should remain equitable. Trust is built through transparency, amongst other things. Would architects sign an equitable bid register, for example, administered by one of the professional bodies and in the interests of transparency between all architects?

What other ways might architects develop better trust in each other to do the right thing in bid processes?

Enforced Action

In the absence of developing trust, it might be necessary to enforce cooperation. This might be through enforcement of fair bid processes – as an alternative to a certifiable process. Architects have ethical obligations to the profession built into the constitutions of professional bodies such as the Australian Institute of Architects (which admittedly not all belong to). It might be that these ethical constitutional obligations extend to equitable practice in tendering. It’s an extreme step to create an enforceable and fair process, but it’s an option. There are real issues around who would run it, how it would be enforced, and so on, aside from the fact it’s easily sidestepped if only run by professional bodies. It’s just another option to float.

The Common Good

Notionally this is where things are at now. Yes, the Prisoner’s Dilemma suggests that self-interest trumps the common good. In a profession that by and large prides itself on its ethics, it’s not beyond the realms of possibility to rein in self-interest. It will take developing better awareness, understanding and agreement to consider the common good of the profession. In this case, self-interest is not a sustainable business model for the profession as a whole or individual practices alike. Building this conversation takes effort and intention. It’s hard work requiring difficult conversations. It might take quiet words to practices that choose self-interest over common good – naming and shaming is seldom productive. It also needs to extend further than social media.

Conclusion

Returning to the Prisoner’s Dilemma, it will take the cooperation of the architecture profession to address the issue of low balling fees and doing free work in order to win bids. Self-interest leads to a worse outcome for the entire profession. One that isn’t financially sustainable and undervalues professional services and the profession.

Michael Lewarne is the Director of unmeasured, a committee member of the ACA – NSW/ACT branch, and facilitator of the Architects Mental Wellbeing Forum in NSW/ACT.