Want to be More Profitable? Here's How.

How can small architectural practices be more profitable? Rena Klein outlines the issues to consider, and some strategies for getting started.

In my consulting practice, many small firm owners ask me how they can become more profitable. While profitability isn’t the only bottom line for most architects, there comes a time for many when they just want to earn more money in exchange for their hard work. And, as firm owners, most also want to be able to reward trusted staff and build the value of their firm as a business entity.

How a firm becomes more profitable is a complex issue involving many factors, including firm culture, leadership proclivities, market sector, client management, and operational effectiveness. Of course, to get different results it is necessary to embrace change and do things differently, which is often the biggest hurdle to overcome.

Influences on Profitability

Design firms operate in an unpredictable environment. This means that unexpected issue on a project or a particularly difficult client can sometimes have a disastrous impact on firm profitability. Often these situations are beyond a practitioner’s control. Bad things do happen to good architects, even when following all best practices.

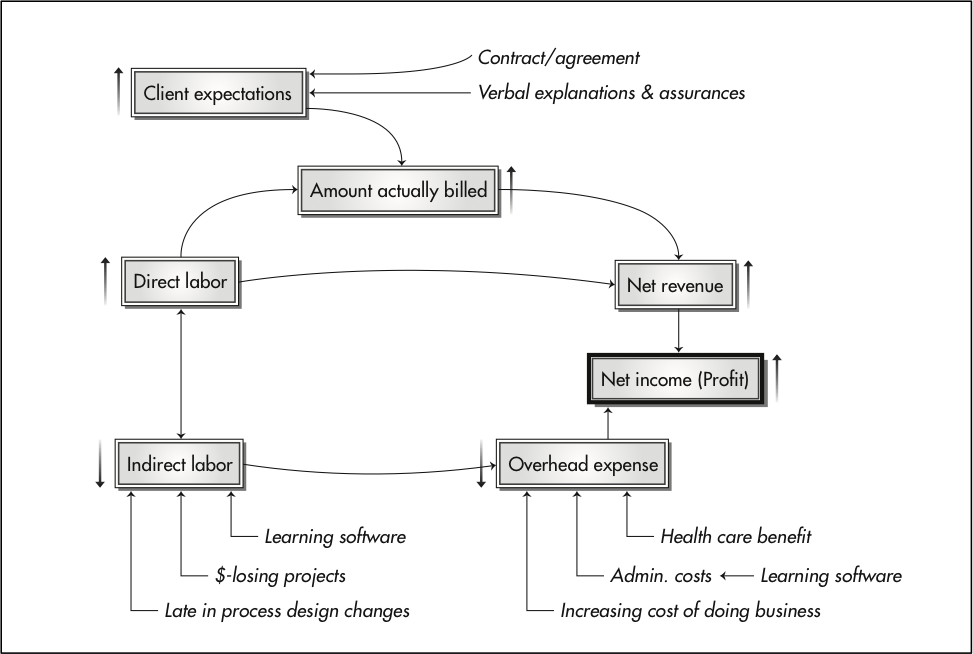

Nevertheless, it is possible to improve profitability by taking action in arenas where firm leaders do have some control. One of these involves reducing the number of hours worked on projects that, for one reason or another, cannot be billed to clients. To help understand how this change can be enacted the chart below shows the influences on profitability in design firms.

Influences on Profitability (Chapter 8, The Architect’s Guide to Small Firm Management, by Rena Klein, Wiley, 2010)

First, a few definitions. Direct labor is hours worked on projects, while indirect labor is all the rest of the hours worked. For employees, indirect labor includes paid time off, and activities such as learning software, researching issues that relate to all projects and attending office meetings. For firm leaders, indirect labor will also include marketing and business development work, as well as time spent mentoring, managing, and otherwise working to develop and improve the firm.

Indirect labor is part of the firm’s overhead expense along with payroll related costs and general expenses needed to run the firm, such as rent, insurance and office supplies. Obviously, as illustrated above, when overhead goes down, profitability goes up. So, one step to improving profitability is to create an annual budget and track actual spending in relation to that budget. In that way, firm leaders can be conscious of their spending, which helps keep the general expenses of the firm under control. Industry best practice tells us that overhead, including indirect labor expense, should be around 48–52% of the firm’s net revenue (architectural fees only, excluding pass through revenue going to consultants).

Direct labor expense is the cost of hours worked directly on projects and should be about 28–32% of net revenue. It is important to remember that direct labor is all that a firm actually has to sell. In general, when the number of direct hours goes up in relation to total hours, net revenue will increase, and so will profitability (especially if many of the direct hours are being performed by junior staff).

Impact of Unbillable Direct Hours

However, in most firms, there is a difference between the number of hours that are worked on projects (direct hours) and the number of hours that are actually billed to clients. This holds true whether a firm invoices clients by the hour or by percentage of completion in a fixed fee contract. In a fixed fee contract, it may be more likely that there are direct hours unbilled to clients, since the project budget can’t be exceeded. However, even in hourly contracts, it is rare that all direct hours are actually billable.

A firm’s potential for increasing profitability is often evident by comparing what might have been billed in a given period of time (say one year) to what actually was collected as net revenue.

When I make these calculations for firms – potential billings compared to net revenue in a given period of time (on an accrual basis), I typically see a discrepancy of 85–90%. This means that about 10–15% of hours recorded as worked on projects were not actually billed to a client. Although I have only anecdotal evidence, it appears that most firms just cannot collect payment for 10–15% of the work they do for clients. The good news is that this can be seen as an opportunity for improvement. The first step is to discover where those unbillable hours are going. Capturing more of these hours as billable to clients will immediately translate into increased profitability.

In the worst cases, actual charges to clients can be as little as 40% of potential billings. This is serious cause for alarm since it is very hard to be profitable, or break-even, when 40% of hours worked on projects cannot be billed to clients for one reason or another. Of course, if you are being paid enough for the remaining 60% of the hours, that’s another story, but it is not the usual one.

Typically, there are four reasons why firms have an excessive number of direct hours that cannot be billed to clients.

1. Scope creep

If scope of services is not carefully articulated in the agreement – or if clients are not asked, or don’t expect to pay more when they request additional services – firm owners are simply leaving money on the table. If you don’t want to work for free, be sure your clients understand exactly what you are agreeing to do in exchange for what they are paying. In other words, distinguish between basic, additional and excluded services. Communicate regularly with your client about the progress of the design process and stay current with invoicing throughout the project.

2. Ineffective work processes

Work processes can be improved with design thinking. Best practice is for the entire staff to work together to identify, design and implement improvements. Practice problem seeking – “What challenges seem to occur over and over again?” “What obstacles hinder people’s productivity?” Then design ways to improve the situation. Underlying issues may include:

- the lack of a process for internal knowledge transfer and adaptation

- principals who are micro-managing and are the bottleneck in production; and

- wasted effort due to late-in-process design changes, or a tendency toward ‘excessive perfection’.

3. Staffing balance

In most firms, the key to sustainable profitability is having a balanced staff in terms of experience level and having the right people doing the right tasks. When principals do what project architects could do, the firm is losing money. When project architects do what interns or technical staff could do, the firm is losing money. Best practice is to shift project management from principal to project architects as soon as possible in a project and for project architects to mentor and enable junior staff to take on more of the workload.

4. Not charging enough

Quite simply, many owners of small firms undervalue their services. They determine their hourly rates and project fees based on what they think the client is willing to pay, without truly considering what it will take to do the project, cover overhead, and include a profit factor. Be certain that the nominal hourly billing rate of each staff member is at least 20% over each person’s cost rate plus overhead (break-even rate). Figure the fee for each phase of the project at each person’s break-even rate and then figure it again with a billing rate that includes a 20% profit. This will give you a fee range for each phase and a bottom line figure you should not go below.

Controlling scope creep, improving work processes, balancing skill and experience of your staff, and making sure that you are charging enough are the keys to becoming more profitable. All involve examining how you are currently doing things and whether those ways are still serving your goals. Take a critical look at your proposals and agreements, how you develop fees and how effectively work is accomplished. While it is sometimes difficult to find time to design and implement improvements, the potential payoff – being paid for more of the time actually worked on projects – is well worth the effort.

Rena M. Klein, FAIA, is the author of The Architect’s Guide to Small Firm Management (Wiley, 2010) and principal of RM Klein Consulting, a firm that specialises in financial management support, process improvement, strategic planning, and helping small design firms prosper.

The article first appeared in Licensed Architect Magazine and is republished with permission.